The American Peony Society Story

International Gate Keeper of the Peony

The American Peony Society was born in a time of exciting, but chaotic, growth in the world of peonies. When the 37 men met in 1903 at Detroit to form the society, their principal goal was to set some standards to name, describe and evaluate the rapidly growing number of peony cultivars.

The American Peony Society was born in a time of exciting, but chaotic, growth in the world of peonies. When the 37 men met in 1903 at Detroit to form the society, their principal goal was to set some standards to name, describe and evaluate the rapidly growing number of peony cultivars.

A year earlier the owner of Cottage Garden Nursery in Long Island, New York, had written a open letter to peony growers stating, “under current conditions, when one orders a peony under a new name, a useless mixture of sorts under various names is often received.”

He and others were being victimized by the adverse effects from the rapidly expanding popularity of peonies in the second half of the 1800s. Spurred by the imports of new cultivars from hybridizers in France and England, commercial nurseries were finding a strong market for peonies among collectors and the gardening public. In turn, the demand prompted commercial plant growers to begin efforts to propagate peonies for the wholesale trade and to begin their own efforts to breed new cultivars. By the turn of the century people such as H. A. Terry of Iowa, John Richardson of Massachusetts and J. F. Rosenfield of Nebraska were marketing their own varieties along with the imports.

Some of the new growers and breeders weren’t careful with record keeping or quality control over what they propagated. Some likely were taking advantage of a public that knew little of these new plants. B. H. Farr, one of the early presidents of the society, summed it up well, writing “owing to the chaotic state of peony nomenclature, no one is sure of getting the plants he ordered…”

The newly-formed society would soon find out, first-hand about chaos. One of their first orders of business was to establish a committee to tackle the nomenclature issue. It wasted little time. By the 1904 meeting of the society, it proposed and began implementing a test-plot project with the cooperation of Cornell University at Ithaca, New York. They called for growers throughout the United States and abroad to donate roots for evaluation. That first year, roots representing almost 1,500 varieties were donated by 22 American growers as well as a number from four foreign countries. Within a couple of years, just shy of 2,000 peony varieties were represented in the trial. Once the evaluation process began, the results confirmed some of the worst concerns. For example, among the peonies identified by the committee as Edulis Superba, they found that the roots had been submitted under 23 different names. When the committee questioned the names on a donation of 96 roots, the source admitted to just making up the names after they received an unlabeled bulk shipment of roots. Along with more minor problems, such as the misspelling of names, they found that the quality of some new varieties was so poor, the committee was recommending that many plants simply be discarded.

By the end of the trial in 1908, the committee had completed descriptions for 750 cultivars in the test plot and rated them on a scale of 1-10. By 1911 it was estimated that 95% of some 2,000 commercial varieties were now properly identified and correctly named by the Nomenclature Committee. Shortly thereafter, the test plot project was abandoned and many of the plants in the plot were sold off.

At the same time the Nomenclature Committee was created, an Exhibition Committee was formed. Its members were equally ambitious. The exhibitions would showcase the wide variety of peonies available and give recognition to top cultivars through an annual flower show. By the second annual meeting, which was held in New York, the stage was set for the society’s first flower show in which seven growers exhibited.

The exhibition project grew quickly. The initial events were mainly held in the East in places like Boston, Philadelphia and New York, but soon reached out to cities in the Midwest like Detroit, Chicago and Cleveland. At the same time, they grew in scope to become major public events. The 1923 exhibition in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul included a parade of floats that featured some 50,000 peony blooms that had been shipped on ice in railcars just for the event.

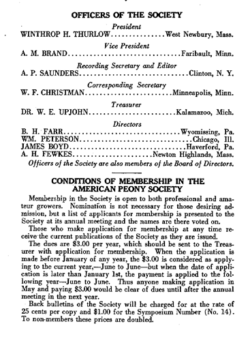

1924 Officers Listed in Bulletin

These events were held in great halls to accommodate the thousands of blooms to be judged in the annual flower show and the large crowds of spectators. The 1924 show in Des Moines drew 15,000 visitors.

In the early years, flower exhibitors vied not only for honors, but also for significant cash premiums. The 1915 show awarded a top prize of $25 for the Open Class best collection of not more than 100 varieties. That’s the equivalent of $420 in 2019 dollars. The floral display not only drew in the public, but also showed growers and hybridizers standards to which they should aspire.

During this era, the planting of peonies exploded, both as a garden plant and for the commercial cut flower markets. By the end of the 1920s membership in the American Peony had surpassed 1,000, and interest in new peony varieties soared. A 1926 catalog for Windy Hills Garden offered the new Alice Harding peony, an herbaceous pink double, for $100, which would equate to $1,428 in the 2019 economy.

Hundreds of acres were now planted into peonies by cut flower farms. The ability of these opulent flowers to hold up to the rigors of shipping long distances by railcar had made them a place at the top in major flower markets across the nation. This created demand for thousands of root divisions to plant cut flower fields of sometime 50 acres and more. By the late 1920s, the Brand Peony Farm was harvesting an average of 250,000 roots each year to meet both garden and flower farm demands.

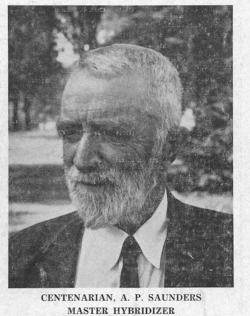

The development of new peony cultivars was also booming. Some like A. P. Saunders, who revolutionized peony hybridizing by combining multiple species, took a scientific approach, carefully selecting varieties to cross and keeping detailed notes that spanned multiple generations of crosses. At the other extreme were growers who gathered and planted bushels of open pollinated seeds. They then grew and sorted through the many thousands of seedlings, selecting some of the most promising and plowing under the rest.

To help its members keep up with all the changes, in 1915 the American Peony Society began publishing a bulletin, which eventually became a quarterly release. Early on that bulletin was used to survey members on their 1-10 ratings of peony cultivars. Those ratings began to be used by sellers to market their peonies, which tended to weed out from the marketplace many of the lower rated varieties. And after a number of these bulletin surveys, the APS came out with a recommendation that varieties scoring 7.5 or lower be discarded. The bulletins also carried articles written by members from throughout the country on dividing, planting, growing and hybridizing methods. Methods of propagation from seeds, divisions, cuttings, layering and grafting also were covered.

Over the years, the APS also has developed a number of publications as part of its educational efforts, beginning in 1928 with “Peonies: A Manual of the American Peony Society,” which covered a wide range on information about the types of peonies, practical information on growing, propagating and breeding them, along with historical and bibliographic information relating to peonies. In more recent years, the society published books specifically on such topics as hybrid peonies, tree peonies and the evolution of peonies.

To help bring focus on some of the elite peony cultivars, the society in 1923 began its Gold Medal Award program, which has now become an annual award for general excellence. The award’s criteria emphasize qualities important to most of the peony-growing pubic, which includes availability, dependable performance, no need for ancillary support of stems, good plant habit, healthy foliage throughout the growing season and reasonable pricing. Since 2009 the APS has been paying special attention to evaluating peonies on their worth as landscape plants. After being monitored by a committee of growers from various parts of the county over time, the best varieties receive the Award of Landscape Merit. There are now 40 cultivars so designated‑-with more to be added as evaluations are completed.

The APS exhibitions, now more commonly referred to as conventions, have evolved over the years. While the flower show remains the main attraction for the public, the events are not the grand public spectacle of the early years. Seminars now provide members with some of the best, most up-to-date information on a wide variety of issues related to peonies and tours of commercial growing operations, as well as both private and public gardens, give them a first-hand look at some of best peony practices. At the auction of peony plants, members have an exclusive opportunity on some of the best varieties available.

The work of the Nomenclature Committee had its biggest success in 1974 when the American Peony Society was chosen by the International Society for Horticulture Science as the worldwide registrar for the genus Paeonia.

With advances in mobile refrigeration and rapid air travel, peonies lost some of their competitive edge over other cut flowers, so the massive plantings for commerce largely disappeared from America by the mid 1900s. The fallout from that decline trickled down to the peony nurseries, some of which were forced out of business. And, for a time, it seemed as if peonies would have to take a lesser place in the hearts of the gardening public. But peony breeders soon shifted their emphasis to create sturdier, more landscape friendly plants through the development of new herbaceous hybrids, the intersectionals and tree peonies, opening more options for the public to use peonies their home gardens.

Cut flower peonies also are making a comeback. With off-season production in places like New Zealand, Chile, Kenya, Israel and Alaska, peonies are now available to fill vases year around. Advances in peony production techniques, especially among large growers in Europe, has led to a big increase in the number of acres being planted for peony cut flowers. The Netherlands alone has seen peony planting rise by 50% in just 5 years to just shy of 3,000 acres. FloraHolland, which is the largest flower market in the world, sold nearly 85 million peony stems in 2018. The Slow Flower movement, which encourages consumers to buy from sources closer to home, has benefited smaller growers in the United States and has made it more viable for people to establish cut flower farms with peonies throughout the country.

Cut flower peonies also are making a comeback. With off-season production in places like New Zealand, Chile, Kenya, Israel and Alaska, peonies are now available to fill vases year around. Advances in peony production techniques, especially among large growers in Europe, has led to a big increase in the number of acres being planted for peony cut flowers. The Netherlands alone has seen peony planting rise by 50% in just 5 years to just shy of 3,000 acres. FloraHolland, which is the largest flower market in the world, sold nearly 85 million peony stems in 2018. The Slow Flower movement, which encourages consumers to buy from sources closer to home, has benefited smaller growers in the United States and has made it more viable for people to establish cut flower farms with peonies throughout the country.

So once again, The American Peony Society finds itself in the midst of exciting times, presenting both opportunities and challenges. Already well under way is a major project to improve and expand the society’s Internet portal to meet the needs of its members and help educate the gardening public. With a long and solid history on which to build, and renewed enthusiasm by its memberships now spanning 40 states and 24 countries, the future looks bright for both the society and for the peony which it represents.